Passed in March of 2021, the American Rescue Plan Act designated $350 billion for State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds. These funds go directly to states, tribal governments, and local municipalities, though small municipalities (also called Non-entitlement units or NEUs) receive their funds through a state office. As of September 16th, the US Treasury reported that $240 billion of the State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds have been distributed to governments for measures to mitigate the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic. Of the four eligible spending categories for these funds, this blog focuses on “Necessary investments in water, wastewater, and broadband infrastructure,” specifically the use of Local Fiscal Recovery Funds for water, wastewater, and stormwater infrastructure. However, utilities may also receive grants or loans via designation of State Fiscal Recovery Funds and according to this tool from the National Conference of State Legislatures, at least 20 states have designated a portion of their State Fiscal Recovery Funds for water-related infrastructure.

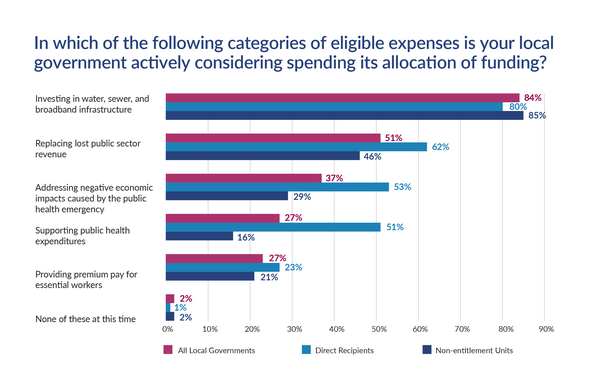

Since Local Fiscal Recovery Funds went directly to municipalities and can be used for more than just infrastructure investment, utilities interested in using these funds for infrastructure projects must consult with their local officials to determine if that investment is priority for the municipality. The good news for local government utilities is that a September 2021 survey by the International City/County Management Association revealed that investing in water, wastewater, and broadband infrastructure was the top category for allocation of local fiscal recovery funds. Given the broad interest in using these funds for infrastructure, it seems appropriate to outline how they can be used, what restrictions apply, and where to find more guidance.

![]()

Many of the questions that have been submitted to the Environmental Finance Center (EFC) from utility staff and/or local government can be officials boiled down to one main question–

What qualifies as an eligible water, wastewater and/or stormwater infrastructure project for funding by Local Fiscal Recovery Funds?

The Interim Final Rule, which is the current guidance from the US treasury regarding how the funds can be spent, points to the EPA’s Drinking Water and Clean Water State Revolving Fund (SRF) handbooks for eligibility guidelines for projects. The handbooks outline many spending categories, which include most capital projects. You can  find much more detail in each of the handbooks.

find much more detail in each of the handbooks.

From the Drinking Water SRF handbook, eligible categories include:

- Treatment

- Transmission and Distribution

- Source

- Storage

- Consolidation

- Creation of New Systems

From the Clean Water SRF handbook, eligible categories include:

- Centralized Wastewater Treatment

- Energy Conservation

- Water Conservation

- Stormwater

- Agricultural Best Management Practices

- Decentralized Wastewater Treatment

- Resource Extraction

- Contaminated Sites

- Landfills

- Habitat Protection and Restoration

- Silviculture

- Desalination

- Groundwater Protection and Restoration

- Surface Water Protection and Restoration

- Planning/Assessment

Additionally, planning and design that will lead to an eligible project is also allowed under both SRF handbooks.

Conversely, given the wide range of potential projects, some local officials and utility staff have been asking–

What isn’t an eligible use of Local Fiscal Recovery Funds for water/wastewater/stormwater projects?

Although many capital project expenses are eligible uses of these funds, other expenses are prohibited, such as debt payments, contributions to reserves, day-to-day operating and maintenance expenses, and purchases of equipment that will be used for more than just the eligible project. Additionally, these funds cannot be used as a non-Federal match for other Federal funds, including SRF loans. Finally, drinking water system expansion is an ineligible expense if the expansion is for a growth in customer base which may or may not materialize. Drinking water expansion is eligible if the customer base to support the growth is already there, but not if the growth is far off. For example, expanding a system to include customers who were on private wells or extending a line to a development in a quickly growing area are eligible projects, but extending a main to an area where the town simply hopes to attract a business park someday is not an eligible project. See section 3.4.1 on page 14 of the Drinking Water SRF handbook for further explanation.

Even with these restrictions, there are still plenty of helpful ways to spend Local Fiscal Recovery Funds on water, wastewater, and stormwater infrastructure projects. However, since they aren’t just typical SRF funds, it’s good to ask–

What else do I need to know?

First off, one of the best places to get further information is the US Treasury’s FAQ document, which details answers to many questions and explains some of what is required and allowed under the Interim Final Rule. A few FAQs that have proved especially helpful are:

- 10- May recipients use funds in conjunction with other funding sources?

- Yes, but only for the eligible part of the project and all ARPA funds must be obligated by December 31, 2024 and spent by December 31, 2026.

- 17- Are eligible infrastructure projects subject to the Davis-Bacon Act?

- Generally, no. The exceptions are projects over $2,000 in D.C. and projects over $10 million—those are subject to reporting guidelines similar to the Davis-Bacon requirements.

- Additionally, NEPA and American Iron and Steel compliance are not required for projects funded only by Local Fiscal Recovery Funds. However, if the funds are used in conjunction with other funds that are subject to the Davis-Bacon, NEPA, and/or AIS requirements, then the project is subject to those requirements as well.

- 4- What provisions of the Uniform Guidance for grants apply to these funds?

- Most of them. Utility staff and local officials should read the US Treasury’s Compliance and Reporting Guidance and make sure any expenditures, including for infrastructure projects, follow the requirements.

Secondly, since the Treasury released the Interim Final Rule (IFR) in May of 2021, grantees have been waiting for the final rule. A few weeks ago, the Treasury released a document that provides more information regarding the finalization of the interim rule. The most important piece of information from this document is that the IFR is, and will remain, binding and effective until the Final Rule is released. If a recipient uses the IFR as guidance for spending their Local Fiscal Recovery Funds while it is in effect, they will not be subject to recoupment. While there are good reasons to wait for clarity from the final rule (or to see how your state will allocate State Fiscal Recovery Funds), if there is an infrastructure project that is clearly eligible under the SRF guidelines, a local government does not need to wait for approval or further guidance to move ahead.

Finally, it is important to keep in mind that while there are opportunities to invest in planning and infrastructure now, any asset that is built will need to be maintained in the future without the guarantee of further federal funding. Utility staff and local government officials can take this opportunity to plan for the future of their utility and consider what investments will lead to a well-maintained and manageable system in the decades to come. The EFC can help utilities plan for future capital needs and determine what may be financially sustainable going forward. You can request assistance here.

Local Fiscal Recovery Funds offer a unique opportunity to invest in towns, cities, and counties, and many municipalities plan to use them to improve their water, wastewater, and/or stormwater infrastructure. There are many possibilities for investment as well as several specific pieces of guidance to follow as these funds are used. The impact of the dollars will ultimately depend on the ability of local governments to maintain the current and future infrastructure needed to provide safe and vital drinking water, wastewater, and stormwater services to their customers.