Here at the Environmental Finance Center, we work with water systems across the country to help them improve their financial and managerial capacity. While there are many reasons why it is important for water systems to have sound management and financial practices, one very important reason is that it can help water systems meet regulatory requirements. Two years ago, my colleague Shadi Eskaf looked at how financial difficulties affect the probability that a water system receives a health violation. This post explores a few other interesting trends in EPA violations in water systems using data from July 1, 2015 to June 30, 2016. To give some context, there were 69,934 violations during this time period—which were committed by 24,725 systems. We compared these violations against EPA’s database of 147,413 publicly regulated drinking water systems.

The first fact we noticed when looking at the data was that smaller community water systems tend to have more violations than larger systems. About 26.3% of systems serving fewer than 500 people had at least one violation, while 16.9% of systems serving more than 100,000 people had at least one violation. As the chart below shows, there is fairly linear progression across the five water system categories.

Figure 1: Percentage of Community Water Systems with Violations

Analysis by Environmental Finance Center @ UNC. Data Gathered from EPA’s SIDWIS database of public water systems and EPA’s database of water system violations July 1st 2015-June 30th 2016. N = 49,562.

Interestingly, this relationship only holds true for community water systems. Among all water systems, systems with fewer than 500 customers actually have the lowest probability of having at least one violation. Given that over 90% of non-community water systems have under 500 users, this means that these non-community water systems receive violations at a lower rate than community water systems. There are several possible reasons for this. Very small non-community water systems often have very simple operations, so there may be less chance for error. Transient systems do not face quite as strict water quality standards, so they may be easier to meet. And perhaps smaller systems are less of an enforcement priority.

Figure 2: Percentage of All Water Systems with a Violation

Analysis by Environmental Finance Center @ UNC. Data Gathered from EPA’s SIDWIS database of public water systems and EPA’s database of water system violations July 1st 2015-June 30th 2016. N = 147,413

The good news for community water systems is that most water systems that commit violations only commit one—at least over the course of a single year. Most water systems commit three or fewer violations, and only 3% of violators commit 10 or more violations in a single year. This indicates that even a marginal improvement in compliance can result in a significant drop in the number of systems that are in violation.

Figure 3: Number of Violations per System

Analysis by Environmental Finance Center @ UNC. Data Gathered from EPA’s SIDWIS database of public water systems and EPA’s database of water system violations July 1st 2015-June 30th 2016. N = 24,752

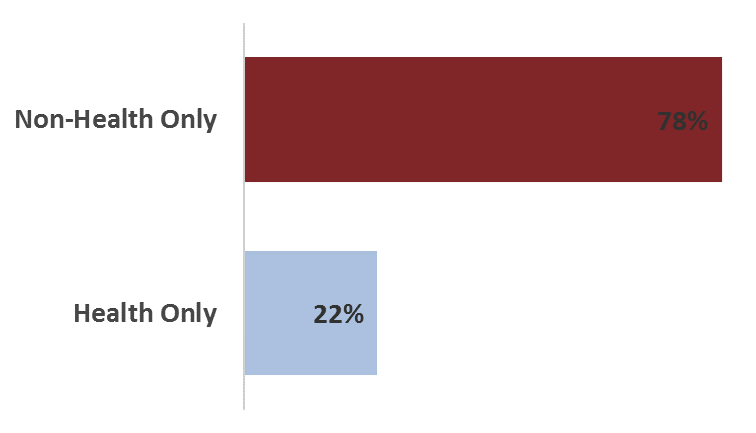

Of the systems with only one violation, most had a “non-health” violation. “Non-Health” violations include monitoring and reporting violations, violations with regard to public notices, and other violations that deal with proper procedures. “Health” violations include maximum contaminant level violations, maximum residual disinfectant level violations, and treatment technique violations.

Figure 4: Percentage of Total Violations

Analysis by Environmental Finance Center @ UNC. Data Gathered from EPA’s SIDWIS database of public water systems and EPA’s database of water system violations July 1st 2015-June 30th 2016. N = 13,688

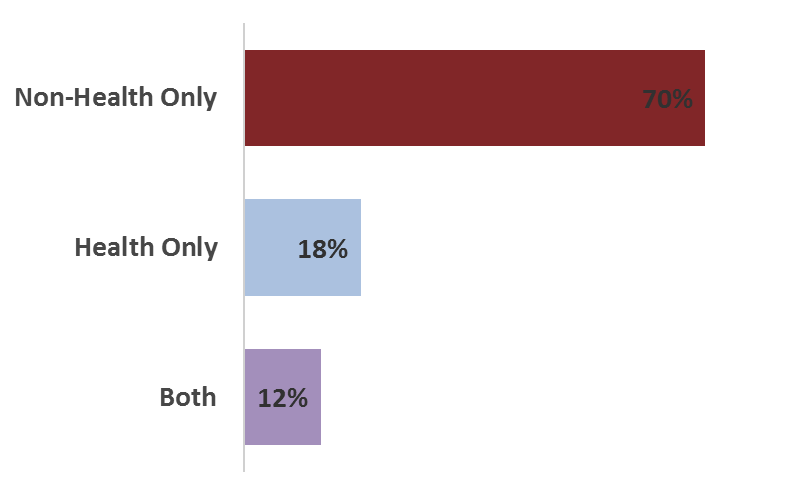

A similar breakdown can be seen among all systems that received a violation. About 70% only had non-health violations, 18% only had health violations, and 12% had a violation of both types.

Figure 5: Types of Violation Received

Analysis by Environmental Finance Center @ UNC. Data Gathered from EPA’s SIDWIS database of public water systems and EPA’s database of water system violations July 1st 2015-June 30th 2016. N = 24,725

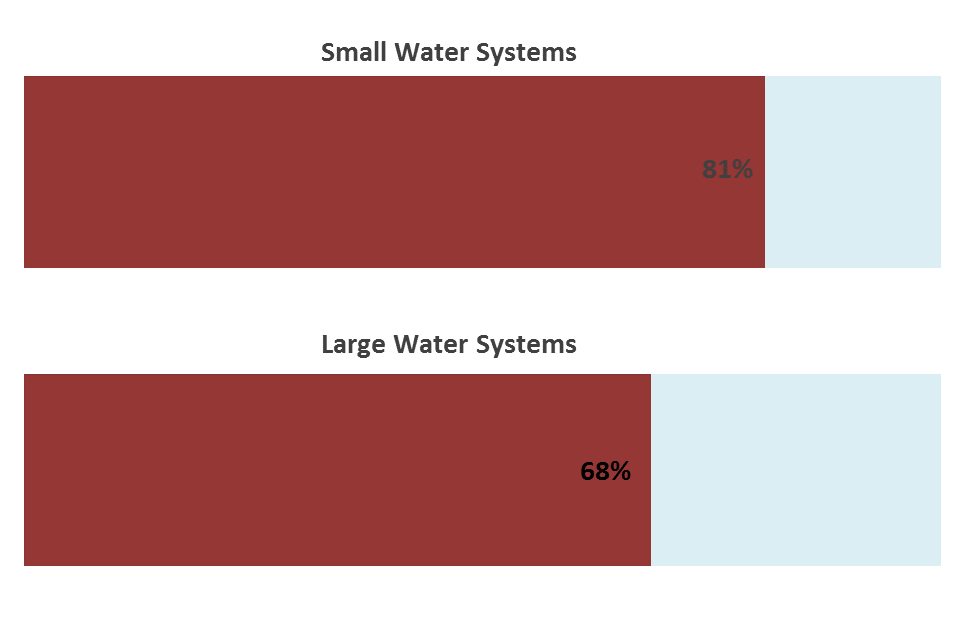

Finally, as part of our ongoing Smart Management for Small Water Systems project, we were interested in seeing if there were any health violation issues specific to community water systems that serve fewer than 10,000 people. As mentioned above, small systems are generally more likely to receive violations. However, not only are they more likely to receive violations—the type of violations they receive tend to be different. For example, 81% of all violations received by small community water systems were for non-health violations, while 68% of all violations received by large community water systems were for non-health violations.

Figure 6: Non-Health Violations for Small and Large Systems

Analysis by Environmental Finance Center @ UNC. Data Gathered from EPA’s SIDWIS database of public water systems and EPA’s database of water system violations July 1st 2015-June 30th 2016. N = 41,387

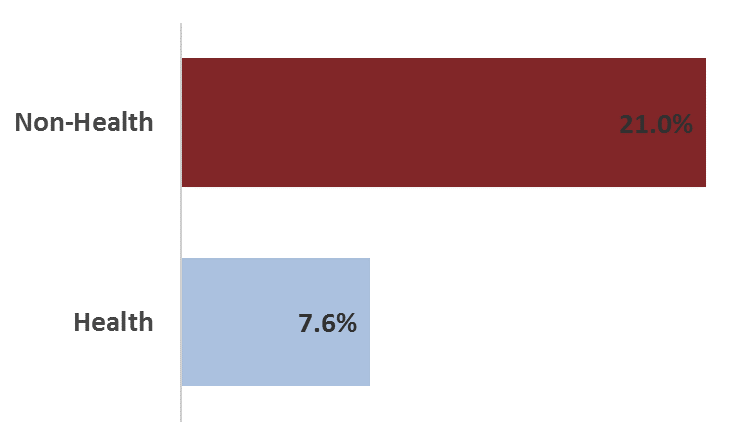

Small community water systems were about 3 times more likely to have a non-health violation than a health violation. 21% of all small community water systems had a non-health violation, while only about 7.6% of these systems had a health violation.

Figure 7: Percentage of Small Systems with a Violation

Analysis by Environmental Finance Center @ UNC. Data Gathered from EPA’s SIDWIS database of public water systems and EPA’s database of water system violations July 1st 2015-June 30th 2016. N = 45,275

Overall, while non-health violations are more common than health violations for all water systems, this discrepancy is even more pronounced among small water systems. We hope that our work at the EFC can help water systems reduce violations of all types—ensuring that everyone receives clean and safe water.